1: EMDR Therapy Overview

The world is round and the place which may seem like the end may also be the beginning.

—Ivy Baker Priest (Parade, 1958)

REINTRODUCTION TO EMDR THERAPY

The goal of

(Shapiro, 2018, p. 6)

This chapter summarizes the information covered in the most recent

Although the

Extensive familiarity with Dr. Shapiro’s primary text is a prerequisite for the reading of this Primer, which is intended to supplement, not replace, her required pre-training readings. No clinician who intends to utilize

There have been other offshoots of

TRAUMA

WHAT IS TRAUMA?

The diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (

the state of severe fright that we experience when we are confronted with a sudden, unexpected, potentially life-threatening event, over which we have no control, and to which we are unable to respond effectively no matter how hard we try (1995).

A child who was sexually abused by her older brother may grow up to believe “I am bad” or “The world is unsafe.” When an individual experiences a traumatic event, the event can become entrenched (or fixed) in the form of irrational beliefs, negative emotions, blocked energy, and/or physical symptoms, such as anxieties, phobias, flashbacks, nightmares, and/or fears. Regardless of the magnitude of the trauma, it may have the potential for negatively impacting an individual’s self-confidence and self-efficacy. The event can become locked or “stuck” in the memory network (i.e., “an associated system of information” [Shapiro, 2018, p. 30]) in its original form, causing an array of traumatic or

TYPES OF TRAUMA

Dr. Shapiro (2018) distinguishes between big “T” traumas and other adverse life experiences or disturbing life events (formerly referred to as small “t” traumas). When a person hears the word “trauma,” experiences and images of man-made events such as fires, explosions, automobile accidents, or natural disasters, which include hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes, emerge. Sexual abuse, a massive heart attack, death of a loved one, Hurricane Katrina, and the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center by international terrorists are graphic examples of big “T” traumas. Among other descriptors, these types of traumas can be defined as dangerous and life threatening and fit the criteria in the

Then there are the traumas Shapiro (2018) has designated as adverse life experiences. These types of events may be subtler and tend to impact one’s beliefs about self, others, and the world. Adverse life experiences are those that can affect our sense of self, self-esteem, self-definition, self-confidence, and optimal behavior. They influence how we see ourselves as a part of the bigger whole. They are often ubiquitous (i.e., constantly encountered) in nature and are stored in state-dependent mode in our memory network. Unless persistent throughout the client’s childhood, adverse life experiences usually do not have much impact on overall development, yet maintain the ability to elicit negative self-attributions and have potential for other long-term negative consequences. The clinical presentations that often signal the presence of past adverse life events may be low self-esteem and anxiety as well as panic disorders and/or phobias, depression, posttraumatic symptoms, and the presence of dissociative disorders. The domains of dysfunction tend to be emotional, somatic, cognitive, and relational.

To illustrate the difference between an adverse life experience and a big “T” trauma, let us consider the case of Rebecca, who grew up as “the minister’s daughter.” As the offspring of a local pastor, Rebecca grew up, figuratively speaking, in a glass house. She believed that her father’s job rested on her behavior inside and outside of her home. In her world, everyone was watching. She was always in the spotlight, and no one seemed to want to share his or her life with her. She went through childhood with few friends. “I remember before and after church, the groups of kids forming. I was the outsider. No one invited me in.” All the kids were afraid that every move they made would be reported to her daddy. Being at home was not much better. Her father was never home. He was always out “tending to his flock” and had little time left for his own family. Her mother was not of much comfort either, because she spent much of her time trying to be perfect as well. Living in a glass house was not easy for any of them, especially Rebecca, the oldest of three. By the time Rebecca entered therapy, she was a wife and mother. She thought she had to be perfect in motherhood and in her marriage as well. She became frustrated, angry, and lonely. She felt misunderstood and neglected by her husband. He was never there. He never listened. She thought she could do nothing right, as hard as she tried.

Probing into Rebecca’s earliest childhood memories, no tragic or traumatic memories (i.e., big “T” traumas) emerged. As she continued to explore her past, the hardships and rigors of living in a glass house as the preacher’s daughter slowly became apparent. The original target that initiated a round of

The differentiation between adverse life experiences and big “T” traumas often appears too simplistic. Another way of discussing the types of trauma is to look at it in terms of shock or developmental trauma.

Shock trauma involves a sudden threat that is perceived by the central nervous system as overwhelming and/or life threatening. It is a single-episode traumatic event. Examples include car accidents, violence, surgery, hurricanes and other natural disasters, rape, battlefield assaults, and war.

Developmental trauma refers to events that occur over time and gradually affect and alter a client’s neurological system to the point that it remains in a traumatic state. This type of trauma may cause interruptions in a child’s natural psychological growth. Examples of developmental trauma are abandonment or long-term separation from a parent, an unstable or unsafe environment, neglect, serious illness, physical or sexual abuse, and betrayal at the hands of a caregiver. This type of trauma can have a negative impact on a child’s sense of safety and security in the world and tends to set the stage for future trauma in adulthood as the sense of fear and helplessness that accompany it goes unresolved.

Table 1.1 outlines more definitely the differences between big “T” traumas and adverse life experiences or disturbing life events (i.e., small “t” traumas).

ADAPTIVE INFORMATION PROCESSING—“THE PAST DRIVES THE PRESENT”

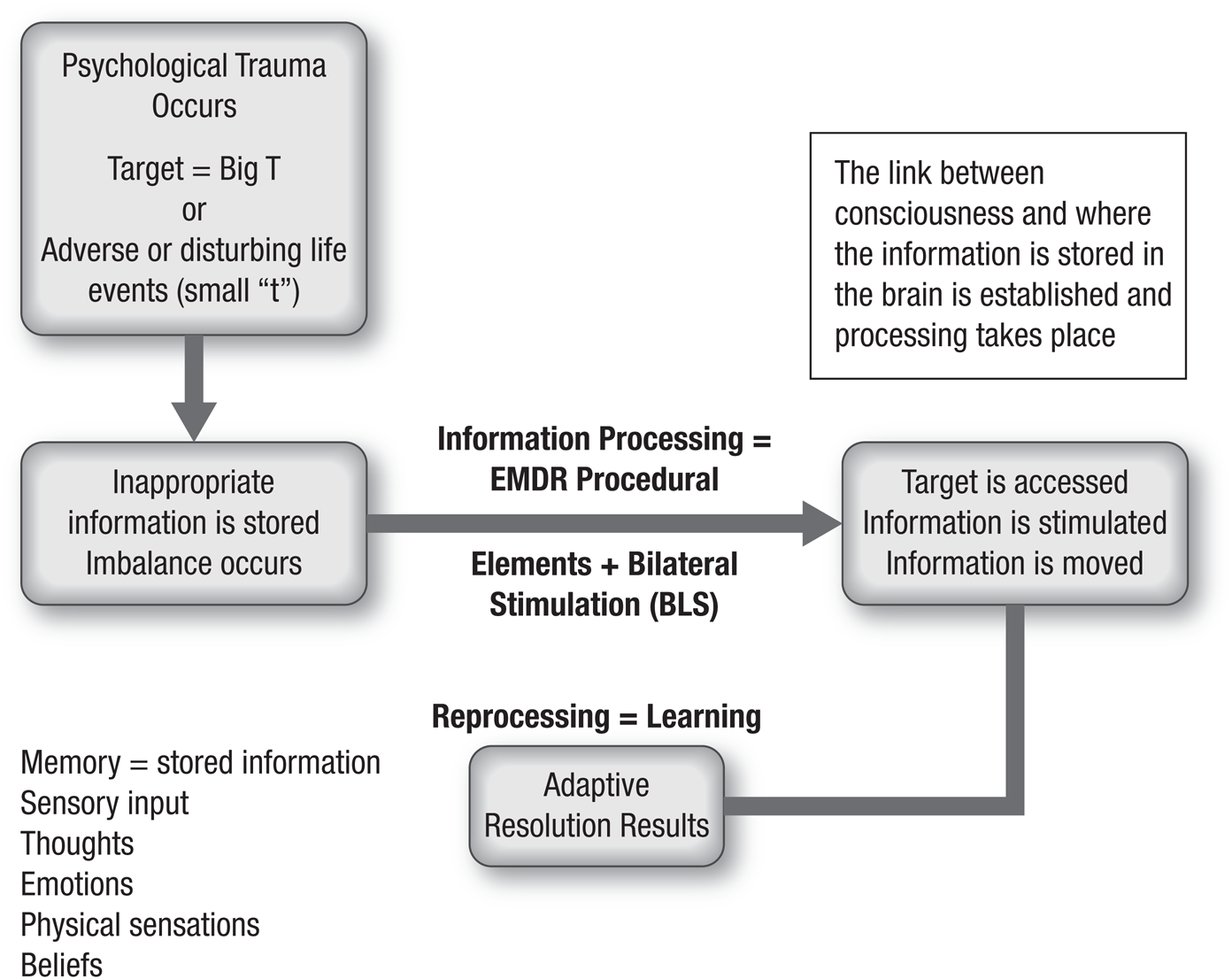

Dr. Francine Shapiro developed a hypothetical information processing model of learning called the

| BIG “T” TRAUMA | SMALL “t” TRAUMA (DISTURBING/DISTRESSING LIFE EVENTS) |

|---|---|

| Major event normally seen as traumatic May be a single- or multiple-event trauma May be pervasive Most often there is intrusive imagery Still elicits similar negative beliefs, emotions, and physical sensations Lasting negative effect on the client’s sense of safety in the world | Disturbing/distressing life event that may not always be perceived as traumatic More common and ubiquitous; usually accumulates over time from childhood More often it is pervasive and ongoing Often there is no intrusive imagery Still elicits similar negative beliefs, emotions, and physical sensations Lasting negative effect on the client’s sense of self (self-confidence, self-esteem, self-definition) |

| Examples: Serious accidents (e.g., automobile or bike accidents, plane crashes, serious falls) Natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, tornadoes, tsunamis, forest fires, volcanic eruptions, floods) Man-made disasters (e.g., 9/11, explosions, fires, wars, acts of terrorism) Major life changes (e.g., serious illnesses, loss of loved ones) Physical and sexual assaults Major surgeries, life-threatening illnesses (e.g., cancer, heart attacks, craniotomies, heart bypasses) Ongoing life events (e.g., sexual abuse, domestic violence) War- and combat-related incidents | Examples: Moving multiple times during childhood Excessive teasing or bullying Persistent physical illnesses Constant criticism Rejections Betrayals Disparaging remarks Losing jobs Divorce or witnessing parental conflict Unmet developmental needs Death of pets Public shaming, humiliation, or failure Unresolved guilt Physical or emotional neglect Getting lost Chronic harassment |

| ACCELERATED INFORMATION PROCESSING (HOW IT IS USED) | |

|---|---|

| Working hypothesis | Working model |

| Explains how | Explains why |

| Developed to explain the rapid manner in which clinical results are achieved | Developed to explain the clinical phenomena observed |

| Simple desensitization treatment effect | Entails an information processing effect |

Abbreviation:

Shapiro (2018) posits that inherent in the

On the other hand, when a trauma occurs that is too large for your system to adequately process, it can become “stuck” (i.e., dysfunctionally stored) in the central nervous system. Maladaptive responses, such as flashbacks or dreams, can be triggered by present stimuli, and there may be attempts of the information processing system to resolve the trauma (Shapiro, 2018). When the system becomes overloaded as just described,

| ADAPTIVE | MALADAPTIVE |

|---|---|

| Big “T” (e.g., safety) | |

| I survived. I can learn from this. I can protect myself. I am safe. | Driving phobia Flashbacks Intense driving anxiety Night terrors |

| Small “t” (i.e., adverse or disturbing/distressing life events; e.g., responsibility) | |

| I am fine as I am. I did the best I could. I am significant/important. | Low self-esteem Irrational guilt Self-neglect, co-dependence |

| TARGET | |

|---|---|

| When the target is a disturbing memory. | When the target is positive (i.e., an alternative desirable imagined future). |

| Negative images, beliefs, and emotions become less vivid, less enhanced, and less valid. | Positive images, beliefs, and emotions become more vivid, more enhanced, and more valid. |

| Before reprocessing, links to dysfunctional material. | Links with more appropriate information. |

| Learning is a continuum. |

The

At the time of disturbing or traumatic events, information may be stored in the central nervous system in state-specific form (i.e., the negative cognitive belief and emotional and physical sensations the client experienced at the time of the traumatic event remain stored in the central nervous system just as if the trauma is happening in the now). Over time, a client may develop repeated negative patterns of feeling, sensing, thinking, believing, and behaving as a result of the dysfunctionally stored material. These patterns are stimulated, activated, or triggered by stimuli in the present that cause a client to react in the same or similar ways as in the past. Shapiro (2018) states throughout her basic text that the negative beliefs and affect from past events spill into the present. By processing earlier traumatic memories,

Abbreviation:

| DYSFUNCTIONALLY STORED MEMORIES | ADAPTIVELY STORED MEMORIES |

|---|---|

| Information processing system is overwhelmed and becomes “stuck” Embraces an inappropriate, developmentally arrested lack of power in the past | Information processing system is able to connect to current information and resources and adequately process information Embraces an age-appropriate power in the present |

| Past-oriented or developmentally arrested, dysfunctional perspective Stored in incorrect form of memory (i.e., implicit/motoric) Past is present | Present-oriented and age-appropriate, adaptive perspective Stored in correct form of memory (i.e., explicit/narrative) Past is past |

| ACCESS Frozen dysfunctional memory |

| STIMULATE Information processing system |

| MOVE Information to adaptive resolution |

| RESULTS Lessening of disturbance Gained information and insights Changes in emotional and physical responses |

Cognitive behavioral techniques, such as systematic desensitization, imaginal exposure, or flooding, require the client to focus on anxiety-provoking behaviors and irrational thoughts or to relive the trauma or other adverse life experiences.

Changes in perception and attitude, experiencing moments of insight, and subtle differences in the way a person thinks, feels, behaves, and believes are byproducts as well. The changes can be immediate. Take, for instance, a session with a young woman who had been brutally raped by her ex-boyfriend. During the Assessment Phase, Andrea’s terror appeared raggedly etched in her face and slumped demeanor. After many successive sets of bilateral stimulation (

Exhibit 1.2 demonstrates in action the inherent information processing mechanism as it highlights the changes that occurred as a result of Andrea and Billy’s dynamic drive toward mental health with

Because the heart of

| BEFORE | AFTER | |

|---|---|---|

| Client experiences negative event, resulting in: Intrusive images Negative thoughts or beliefs Negative emotions and associated physical sensations | Negative experience is transmuted into an adaptive learning experience | Client experiences adaptive learning, resulting in: No intrusive images No negative thoughts or beliefs No negative emotional and/or physical sensations An empowering new positive self-belief |

| What happens? Information is insufficiently (dysfunctionally) stored Dysfunctional information gets replayed Developmental windows may be closed | What happens? Information is sufficiently (adaptively) processed Adequate learning has taken place Development continues on a normal trajectory | |

| Resulting in: Depression Anxiety Low self-esteem Self-deprecation Powerlessness Inadequacy Lack of choice Lack of control Dissociation | Resulting in: Sense of well-being Self-efficacy Understanding Catalyzed learning Appropriate changes in behavior Emergence of adult perspective Self-acceptance Ability to be present |

Abbreviation:

Using an example of a traumatic event, 1.8 illustrates more graphically what happens during reprocessing of a traumatic event.

For a more comprehensive explanation of

As the previous tables and figures demonstrate,

MODEL, METHODOLOGY, AND MECHANISM OF EMDR THERAPY

Why and how does

| NEGATIVE EXPERIENCE | ADAPTIVE LEARNING EXPERIENCE | |

|---|---|---|

| Example: After a heated argument, Mary is raped by her ex-boyfriend in the parking lot of a bar they just left. | ||

| Mary experiences: Intrusive images: Negative thoughts and self-beliefs (e.g., I am a bad person) Negative emotions (e.g., shame, fear, anger, anxiety) Negative physical sensations (e.g., heart palpitations, sweaty palms, difficulty breathing) Sense of powerlessness Lack of choice Lack of control Inadequacy | Learning is catalyzed | Mary experiences: Cognitive restructuring of perceptions Association to positive affects Sense of well-being and self-efficacy New insights Feelings of empowerment Learning Greater sense of understanding |

Model—The

AIP model provides the theoretical model forEMDR therapy.Methodology—Eight phases of

EMDR therapy plus the ethics, safeguards, and validated modifications for basic and specific clinical situations and populations.Mechanism—Current hypotheses on how and why

EMDR therapy works on a neurobiological level.

MODEL—HOW?

The

Guided by this information processing model, memory networks are believed to form the basis of clinical symptoms and mental health in general, and “unprocessed memories are considered to be the primary basis of pathology” (Shapiro, 2009–2017a). The important components of the model as outlined by Shapiro (1995, 2001, 2018, 2009–2017a, 2009–2017b) are summarized in Table 1.9.

There is a body of literature, including both research and case reports on a variety of clinical complaints, that illustrates the predictive value of the

| The |

| Disturbing memories are dysfunctionally stored (i.e., perceived in the same way as when the memory was originally formed) and may disrupt the information processing system. |

| Emotions, physical sensations, and thoughts and beliefs associated with unprocessed memories are experienced by the client as their perceptions in the present link to the historical memory networks. |

| In order to be interpreted, a client’s perceptions of resent situations link into networks of physically stored memories (negative or dysfunctional) from the past. In other words, the past is present. |

| As the processing begins, disruptions may be caused by high levels of emotional disturbance or dissociation, which can block adaptive processing. |

| When a client is processing the memory of a traumatic event, they have the opportunity to forge adaptive associations with memory networks of functional information stored in the brain. This |

| During processing, the unprocessed elements of a client’s memory (i.e., image, thoughts, sounds, emotional and physical sensations, beliefs) have the ability to transform/transmute to an adaptive resolution. At this point, learning may take place. By discarding maladaptive information and storing adaptive information, a client has new learning that may better inform future experiences and choices. |

Abbreviation:

METHODOLOGY—HOW/WHAT?

For further reading on the “how” and “what” of

| 1997 Brown, K. W., McGoldrick, T., & Buchanan, R. (1997). Body dysmorphic disorder: Seven cases treated with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(2), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800018403 |

| 1998 Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences ( |

| 2001 Ray, A. L., & Zbik, A. (2001). Cognitive behavioral therapies and beyond. In C. D. Tollison, J. R. Satterhwaite, & J. W. Tollison (Eds.). Practical pain management (3rd ed., pp. 189–208). Lippincott. Shapiro, F. (2001). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. |

| 2002 Perkins, B., & Rouanzoin, C. (2002). A critical evaluation of current views regarding eye movement desensitization and reprocessing ( Shapiro, F. (2002). |

| 2004 Heim, C., Plotsky, P. M., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2004). Importance of studying the contributions of early adverse experience to neurobiological findings in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29, 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300397 |

| 2005 Gold, S. D., Marx, B. P., Soler-Baillo, J. M., & Sloan, D. M. (2005). Is life stress more traumatic than traumatic stress? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19, 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.06.002 Mol, S. S. L., Arntz, A, Metsemakers, J. F. M, Dinant, G., Vilters-Van Montfort, P. A. P., & Knottnerus, A. (2005). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder after non-traumatic events: Evidence from an open population study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 494–499. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.6.494 |

| 2006 Brown, S., & Shapiro, F. (2006). Madrid, A., Skolek, S., & Shapiro, F. (2006). Repairing failures in bonding through Raboni, M. R., Tufik, S., & Suchecki, D. (2006). Treatment of Ricci, R. J., Clayton, C. A., & Shapiro, F. (2006). Some effects of Shapiro, F. (2006). New notes on adaptive information processing: Case formulation principles, scripts, and worksheets. Uribe, M. E. R., & Ramirez, E. O. L. (2006). The effect of Wilensky, M. (2006). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing ( |

| 2007 Fernandez, I., & Faretta, E. (2007). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Clinical Case Studies, 6(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650105277220 Schneider, J., Hofmann, A., Rost, C., & Shapiro, F. (2007). Shapiro, F. (2007a). Shapiro, F. (2007b). Shapiro, F., Kaslow, F. W., & Maxfield, M. (2007). Handbook of |

| 2008 Bae, H., Kim, D., & Park, Y. C. (2008). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for adolescent depression. Psychiatry Investigation, 5(1), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2008.5.1.60 Gauvreau, P., & Bouchard, S. (2008). Preliminary evidence for the efficacy of McGoldrick, T., Begum, M., & Brown, K. W. (2008). |

| 2008 Russell, M. C. (2008). Treating traumatic amputation-related phantom limb pain: A case study utilizing eye movement desensitization and reprocessing within the Armed Services. Clinical Case Studies, 7(2), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650107306292 Schneider, J., Hofmann, A., Rost, C., & Shapiro, F. (2008). Solomon, R. M., & Shapiro, F. (2008). |

| 2009 Wesselmann, D., & Potter, A. E. (2009). Change in adult attachment status following treatment with |

| 2010 de Roos, C., Veenstra, A., de Jongh, A., den Hollander-Gijsman, M., van der Wee, N., Zitman, F., & van Rood, Y. R. (2010). Treatment of chronic phantom limb pain using a trauma-focused psychological approach. Pain Research & Management, 15(2), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/981634 Obradovic, J., Bush, N. R., Stamperdahl, J., Adler, N. E., & Boyce, W. T. (2010). Biological sensitivity to context: The interactive effects of stress reactivity and family adversity on socioemotional behavior and school readiness. Child Development, 1, 270–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01394.x Robinson, J. S., & Larson, C. (2010). Are traumatic events necessary to elicit symptoms of posttraumatic stress? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2, 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018954 Teicher, M. H., Samson, J. A., Sheu, Y.-S., Polcari, A., & McGreenery, C. E. (2010). Hurtful words: Association of exposure to peer verbal abuse with elevated psychiatric symptom scores and corpus callosum abnormalities. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1464–1471. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010030 |

| 2011 Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Fisher, H. L., Polanczyk, G., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2011). Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567 Heins, M., Simons, C., Lataste, T., Pfeifer, S., Versmissen, D., Lardinois, M., Marcelis, M., Delespaul, P., Krabbendam, L., van Os, J., & Myin-Germeys, I. (2011). Childhood trauma and psychosis: A case-control and case-sibling comparison across different levels of genetic liability, psychopathology, and type of trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 1286–1294. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101531 |

| 2011 Nazari, H., Momeni, N., Jariani, M., & Tarrahi, M. J. (2011). Comparison of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing with citalopram in treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 15(4), 270–274. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2011.590210 |

| 2012 Afifi, T. O., Mota, N. P., Dasiewicz, P., MacMillan, H. L., & Sareen, J. (2012). Physical punishment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative Shapiro, F. (2012a). van den Berg, D. P. G., & van der Gaag, M. (2012). Treating trauma in psychosis with Varese, F., Smeets, F., Drukker, M., Lieverse, R, Lataster, T., Viechtbauer, W., Read, J., van Os, J., & Bentall, R. P. (2012). Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: A meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective-and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(4), 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs050 |

| 2013 Doering, S., Ohlmeier, M.-C., de Jongh, A., Hofmann, A., & Bisping, V. (2013). Efficacy of a trauma-focused treatment approach for dental phobia: A randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 121(6), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/eos.12090 Faretta, E. (2013). |

| 2014 Read, J., Fosse, R., Moskowitz, A., & Perry, B. (2014). The traumagenic neurodevelopmental model of psychosis revisited. Neuropsychiatry, 4(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.2217/NPY.13.89 Shapiro, F. (2014). The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing ( |

| 2015 Allon, M. (2015). Behnam Moghadam, M., Alamdari, A. K., Behnam Moghadam, A., & Darban, F. (2015). Effect of |

| 2018 Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedure (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. Gauhar, M., & Wajid, Y. (2016). The efficacy of |

MECHANISM—WHY?

Over the past 25 years, numerous studies have indicated that eye movements have effects on a client’s memory in terms of vividness, retrieval, emotional arousal, and more. Studies that evaluated

| 1996 Andrade, J., Kavanagh, D., & Baddeley, A. (1997). Eye-movements and visual imagery: A working memory approach to the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044–8260.1997.tb01408.x Armstrong, M. S., & Vaughan, K. (1996). An orienting response model of eye movement desensitization. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 27, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(95)00056-9 MacCulloch, M. J., & Feldman, P. (1996). Eye movement desensitization treatment utilizes the positive visceral element of the investigatory reflex to inhibit the memories of post-traumatic stress disorder: A theoretical analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(5), 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.169.5.571 Wilson, D., Silver, S. M., Covi, W., & Foster, S. (1996). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Effectiveness and autonomic correlates. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 27, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(96)00026-2 |

| 1999 Lipke, H. (1999). Comments on “thirty years of behavior therapy” and the promise of the application of scientific principles. The Behavior Therapist, 22, 11–14. Rogers, S., Silver, S., Goss, J., Obenchain, J., Willis, A., & Whitney, R. (1999). A single session, controlled group study of flooding and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in treating posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam war veterans: Preliminary data. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13, 119–130. |

| 2000 Bergmann, U. (2000). Further thoughts on the neurobiology of |

| 2001 Kavanagh, D. J., Freese, S., Andrade, J., & May, J. (2001). Effects of visuospatial tasks on desensitization to emotive memories. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466501163689 |

| 2002 Rogers, S., & Silver, S. M. (2002). Is Stickgold, R. (2002). |

| 2004 Barrowcliff, A. L., Gray, N. S., Freeman, T. C. A., & MacCulloch, M. J. (2004). Eye movements reduce the vividness, emotional valence and electrodermal arousal associated with negative autobiographical memories. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 15(2), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940410001673042 Suzuki, A., Josselyn, S. A., Frankland, P. W., Masushige, S., Silva, A. J., & Satoshi, K. (2004). Memory reconsolidation and extinction have distinct temporal and biochemical signatures. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(20), 4787–4795. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5491-03.2004 |

| 2006 Lee, C. W., Taylor, G., & Drummond, P. D. (2006). The active ingredient in Servan-Schreiber, D., Schooler, J., Dew, M. A., Carter, C., & Bartone, P. (2006). |

| 2007 Propper, R., Pierce, J. P., Geisler, M. W., Christman, S. D., & Bellorado, N. (2007). Effect of bilateral eye movements on frontal interhemispheric gamma |

| 2008 Bergmann, U. (2008). The neurobiology of Sack, M., Hofmann, A., Wizelman, L., & Lempa, W. (2008). Psychophysiological changes during Sack, M., Lempa, W., Steinmetz, A., Lamprecht, F., & Hofmann, A. (2008). Alterations in autonomic tone during trauma exposure using eye movement desensitization and reprocessing ( Elofsson, U. O. E., von Scheele, B., Theorell, T., & Sondergaard, H. P. (2008). Physiological correlates of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.012 |

| 2008 Stickgold, R. (2008). Sleep-dependent memory processing and |

| 2009 Friedman, D., Goldman, R., Stern, Y., & Brown, T. (2009). The brain’s orienting response: An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Human Brain Mapping, 30(4), 1144–1154. Gunter, R., & Bodnar, G. (2009). Lilley, S. A., Andrade, J., Turpin, G., Sabin-Farrell, R., & Holmes, E. A. (2009). Visuospatial working memory interference with recollections of trauma. British Journal of clinical psychology, 48(3), 309–321. |

| 2010 Bergmann, U. (2010). Hornsveld, H. K., Landwehr, F., Stein, W., Stomp, M., Smeets, S., & van den Hout, M. A. (2010). Emotionality of loss-related memories is reduced after recall plus eye movements but not after recall plus music or recall only. Journal of Kapoula, Z., Yang Q., Bonnet, A., Bourtoire, P., & Sandretto, J. (2010). van den Hout, M. A., Engelhard, I. M., Smeets, M. A., Hornsveld, H., Hoogeveen, E., & de Heer, E. (2010). Counting during recall: Taxing of working memory and reduced vividness and emotionality of negative memories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(3), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1677 |

| 2011 El Khoury-Malhame, M., Lanteaume, L., Beetz, E. M., Roques, J., Reynaud, E., Samuelian, J.-C., Blin, O., Garcia, R., & Khalfa, S. (2011). Attentional bias in post-traumatic stress disorder diminishes after symptom amelioration. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49(11), 796–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.006 Kristjánsdóttir, K., & Lee, C. M. (2011). A comparison of visual versus auditory concurrent tasks on reducing the distress and vividness of aversive autobiographical memories. Journal of |

| 2012 van den Hout, M., & Engelhard, I. (2012). How does van den Hout, M. A., Rijkeboer, M. M., Engelhard, I. M., Klugkist, I., Hornsveld, H., Toffolo, M. J., & Cath, D. C. (2012). Tones inferior to eye movements in the |

| 2013 de Jongh, A., Ernst, R., Marques, L., & Hornsveld, H. (2013). The impact of eye movements and tones on disturbing memories involving Pagani, M., Hogberg, G., Fernandez, I., & Siracusano, A. (2013). Correlates of |

| 2014 Leer, Engelhard, and van den Hout provided corroborating evidence that recall with |

| 2016 van Schie, K., Engelhard, I. M., Klugkist, I., & van den Hout, M. A. (2016). Blurring emotional memories using eye movements: Individual differences and speed of eye movements. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7, 29476. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.29476 van Veen, S. C., Engelhard, I. M., & van den Hout, M. A. (2016). The effects of eye movements on emotional memories: Using an objective measure of cognitive load. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7, 30122. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.30122 |

| 2018 Calancie, O. G., Khalid-Khan, S., Booij, L., & Munoz, D. P. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing as a treatment for |

Abbreviation:

THREE-PRONGED APPROACH

PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

Regardless of what you as a participant were taught in the earlier didactic trainings, what you most likely will remember is what was on the instructional sheet that sat on your lap. The first question that you asked the client was, “What old issue or old memory would you like to focus on today?” It is important to note that this question was only used in the training exercises and not in daily clinical practice. Fortunately, this teaching method has changed as the training focus now is to establish a more formalized plan that attempts to identify past events (and a touchstone event, if available), present triggers, and a future template, and to encourage the participant to process in this order. Shapiro (2006) referred to this strategy as the Treatment Planning Guide (

To completely resolve a client’s issue and achieve adaptive resolution,

THREE-PRONGED TARGETS—EXPERIENTIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO PRESENT-DAY PROBLEMS

The order of the processing is important. First, it is necessary to strive to adaptively resolve past traumas, then process current stimuli that trigger distress, and finally do a future template on the present trigger. See Exhibit 1.3 for a breakdown of what is identified and processed under each prong of the

The clinician may want to consider targeting the memories that lay the groundwork for any present problems and/or issues first. It may be a single traumatic event or what is called a touchstone event, a primary and self-defining event in the client’s life. In

Once all presently charged past events are processed (i.e., after the touchstone event is processed), other past events may or may not have a cognitive or affective charge remaining. The clinician may want to consider processing those that have a “charge” before continuing to recent events. Then any recent events, circumstances, situations, stressors, or other triggers that might elicit a disturbance are targeted. After the past events and present disturbances have been identified and reprocessed, focus on the future desired behavior and the client’s ability to make better choices or cope more effectively. This entails education, modeling, and targeting what Dr. Shapiro calls a future or positive template (2018). It is important for the client to appropriately and properly assimilate the new information gained through the previous prongs (i.e., past, present, and future) by providing them with experiences that ensure future successes.

During recent

Although the standard

The Importance of Past, Present, and Future in EMDR Therapy

The foundation of the three-pronged protocol postulates that earlier memories are processed before current events, and current events are processed before future events. Why is it so important to process these events in this order? What is the effect on the overall treatment result if it is not processed in order of past, present, and future? Earlier life experiences set the groundwork for present events and triggers. Hence, it is useful to reprocess as many of the historical associations with the triggers as possible. Once these associations have been transformed, some, if not many, present triggers will dissipate. There may, however, still be current triggers that exist outside of these channels of association that will need to be targeted and processed independently. Or there may be unprocessed material that surfaces when processing these triggers. These triggers will be the next targets to be processed.

The focus on the future template provides the client an opportunity to imaginally rehearse future circumstances and desired responses. This is yet another opening for unprocessed material to surface. The use of the future template provides the client a means of resolving any anticipatory anxiety that they may still experience in similar future situations. The three-pronged approach appears to be a bottom-up process in that the future is subsumed by the present and the present is subsumed by the past. It has been suggested that bypassing the three-pronged approach as part of the full

TARGETING POSSIBILITIES

TARGETS MAY ARISE IN ANY PART OF THE EMDR THERAPY PROCESS

When a clinician instructs a client to focus on a target in

Throughout Dr. Shapiro’s clinical books (2006, 2018), she refers to several different targets that may arise in certain parts of the process. The past, present, and future targets referred to earlier are the primary focus in the

TYPES OF EMDR TARGETS

As you think about your client sessions, do you recognize any of the types of targets, including the ancillary targets (i.e., other factors that may be contributing to a client’s disturbance) listed in Exhibit 1.5? The following definitions are provided as a refresher:

TARGETS FROM THE PAST

Touchstone Memory

A memory that lays the foundation for a client’s current presenting issue or problem. This is the memory that formed the core of the maladaptive network or dysfunction. It is the first time a client may have believed, “I am not good enough,” or that this conclusion was formed. The touchstone event often, but not necessarily, occurs in childhood or adolescence. Reprocessing will be more spontaneous for the client if the touchstone events can be identified and reprocessed earlier in the treatment.

Example: As an adult, Mary Jane reported being uncomfortable engaging with large groups of people (i.e., 20 or more). She frequently experienced high levels of anxiety before and during office meetings, in church, and at social events. She was nervous, tentative, fearful, and unsure because she could not trust herself to be in control. During the history-taking process, it was discovered that, when she was in the second grade, Mary Jane wet her pants often. She was afraid to use the restroom because she feared its “tall, dark stalls.” Students often teased her, calling her “baby” and yelling out to the other students that she had wet her pants. What she came to believe about herself was, “I cannot trust myself.” This belief carried over into her later life and caused her to react tentatively in group situations.

Primary Events

These are stand-alone events that may emerge during the History-Taking and Treatment Planning, Reprocessing, and Reevaluation Phases, as well as over the course of treatment itself.

Example: Eddie entered therapy months before complaining of headaches and nightmares caused by memories of long-term sexual abuse by his paternal uncle. During treatment, Eddie reported an event involving an automobile accident that occurred 13 years ago. As a result, Eddie still had some anxiousness around driving. This was targeted once the sexual abuse issues had been resolved.

TARGETS FROM THE PRESENT

Circumstances

Situations that stimulate a disturbance.

Example: Having his principal observe one of his classes caused Pierre to flush with anxiety, even though he had been Teacher of the Year three times running and was a 25-year veteran in the public school system as a high school teacher.

Internal or External Triggers

Internal and external cues that can stimulate dysfunctionally stored information and eliciting emotional or behavioral disturbances.

Examples: Sights, sounds, smells, or sensations may be triggers. A client reports becoming triggered by driving on or near a section of roadway where they were involved in a fatal crash in which their best friend was killed. Or a client becomes anxious and ashamed when being questioned by a police officer, even though they have not done anything wrong. The client may react to their own physiological stimuli. For example, they may be triggered by a slightly elevated increase in heart rate, which they fear might lead to a panic attack. One cancer survivor was triggered by an unexplained headache and loss of appetite, leading to fears of recurrence of cancer.

TARGETS FROM THE FUTURE

Future Desired State

How would the client like to be feeling, sensing, believing, perceiving, and behaving today and in the future? What changes would be necessary? The third prong of

Example: Ryan had always been a passive guy who never could say, “No.” “Peace at any cost” was his motto. The touchstone event identified with his conflict-avoidant behavior was a memory of his usually calm mother lunging at his father with a butcher knife during the heat of his father’s verbal attack. Before the night was over, his father had beaten his mother so severely that she was hospitalized for three days. Once this memory had been targeted and reprocessed, Ryan felt more empowered but needed instruction on how to stand up for himself more assertively. After assertiveness training, he was able to imagine himself successfully interacting and responding appropriately in conflict-laden circumstances.

Positive Template (i.e., Imaginal Future Template Development)

A process in which the client uses the adaptive information learned in the previous two prongs to ensure future behavioral success by incorporating patterns of alternative behavioral responses. These patterns require a client to imagine responding differently and positively to real or perceived negative circumstances or situations or significant people.

Example: Joe came home from a business trip and found his wife in bed with his best friend. Joe and his wife had reconciled despite the obvious upheaval it had caused in their already shaky relationship. In the processing of this abrupt discovery, Joe had mostly worked through his reactions and feelings toward his ex-best friend, but he never wanted to interact with him again. However, both worked at the same firm, and it was inevitable that their paths would cross. What the clinician had Joe imagine was a chance meeting with this man and how Joe would like to see this encounter transpire from beginning to end.

OTHER POTENTIAL TARGETS

Node

In terms of the

Example: Jeremy initially entered therapy because he had difficulty interacting professionally with his supervisor. Whenever his boss called or e-mailed asking him to come to his office, Jeremy felt like a small child being summoned to the principal’s office. “What did I do now?” he thought. After a thorough investigation of his past and present, Jeremy related how he felt and reacted around his father. “I always felt as though I had done something wrong.” Jeremy’s father worked and traveled extensively and was not home very much. When he was, Jeremy could find his father in his office working steadily and mostly unaware of the rest of the family activities in their home. His father was gruff and matter of fact and never paid much attention to Jeremy. When he wanted something from Jeremy or would reprimand him for something he did, he would call Jeremy to his office. It was one of those memories that became the target for Jeremy’s presenting issue.

Cluster Memories

These memories form a series of related or similar events and have shared cues, such as an action, person, or location. Each event is representational or generalizable to the other. These nodes are not targeted in the sessions in which they have been identified. The clinician usually keeps an active list of any nodes that arise during reprocessing and reevaluates them later to see if further treatment is necessary.

Example: Anna between the ages of 7 and 10 years was stung by a bee three different times. Each of these events has varying degrees of trauma attached, but each possesses a shared cue, the bees. These are cluster memories and can be grouped together as a single target.

Progression

A progression is a potential node. It generally arises during the reprocessing of an identified target during or between sets (Shapiro, 2018).

Example: Tricia was targeting incidents related to her mother publicly humiliating her when the memory of how her mother acted at her grandfather’s funeral arose. The clinician knew from previous sessions that Tricia had a close, loving relationship with her grandfather and that he was her primary advocate in the family. The clinician wrote down in her notes that her grandfather’s funeral may need to be targeted in and of itself. When a progression (i.e., potential target) arises, it is important not to distract the client from her processing of the current target. Rather, the clinician continues to allow the client to follow the natural processing of the present target and note any disturbance around this event that she may need to explore and target during a future session.

Feeder Memory

This type of memory has been described by Shapiro (2018) as an inaccessible or untapped earlier memory that contributes to a client’s current dysfunction and that subsequently blocks its reprocessing. Unlike progressions, which typically arise spontaneously, feeder memories usually are discovered more by direct inquiry and are touchstone memories that are yet to be identified. If a client becomes stuck during reprocessing, there may be a feeder memory stalling the processing. A feeder memory also differs from a progression in that the feeder memory is an untapped memory related to the current memory being processed. When this type of memory emerges during reprocessing, it should be investigated immediately, especially if a client is blocking on an adolescent or adult memory (Shapiro, 2009–2017a, 2009–2017b). A feeder memory is usually treated before the current memory (i.e.,

Sometimes the identification and spontaneous processing of the feeder memory is sufficient to unblock the processing of the current memory. The feeder memory still needs to be checked following completion of the current memory to determine if it holds any additional disturbance. Sometimes, the current memory needs to be contained and the feeder memory reprocessed (i.e., Phases 3–6) before resuming reprocessing of the current memory.

Example: Brittany was in the midst of reprocessing a disturbing event involving malicious accusations by her mother (i.e., “You’re a slut.” “You must have brought it on somehow.” “You deserved everything that happened.”). These comments were made by her mother after Brittany at the age of 18 years was nearly raped while walking home from school two months earlier. Following several sets of reprocessing and clinical strategies to unblock or shift her processing, Brittany’s level of disturbance did not change. The clinician strategically asked Brittany to focus on the words “I am dirty” (her original negative cognition) and to scan for earlier events in her life that were shameful and humiliating. The memory that finally emerged was the memory of her brothers waving her dirty underwear out a second-story window of their home for all the neighborhood boys to witness. The memory of her brothers’ cruel behavior is what is called a feeder memory.

Blocking Belief

A blocking belief is a belief that stops the processing of an initial target. It is a distorted or irrational conclusion about self, others, or life circumstances (e.g., “It’s not safe to get over this problem.” “If I feel better, I will forget (betray, dishonor, be disloyal) ___________ (fill in the blank).” “I don’t deserve to get over this problem.”). This type of belief may resolve spontaneously during reprocessing or may require being targeted separately. Blocking beliefs typically show themselves when the clinician is evaluating the Subjective Units of Disturbance (

Example: Heather, a sergeant in the military, returned home after sustaining injuries during a rocket attack while on a routine field mission in Afghanistan. Two of her fellow soldiers died from the blast. Heather was hit by flying shrapnel that literally left a hole in her leg. She required two subsequent surgeries, neither of which resulted in removing all the rocket shrapnel from her leg. During recuperation, Heather reported disturbing recurring dreams, flashbacks, and thoughts of the rocket attack, which were frequently accompanied by high levels of anxiety or a panic attack. While reprocessing the event, the sergeant’s negative cognition was “I’m unsafe” and her

Peelback Memory

A peelback memory usually occurs when a touchstone has not been identified and, during reprocessing, other associations begin to “peel back” to expose prior disturbing memories. There is often confusion between a progression and a peelback memory. A peelback memory is an earlier unsuspected memory, whereas a progression is any new associated memory.

Example: After the processing of an earthquake, Taylor continued to exhibit symptoms of

Fears

Fear in the processing of targeted information can become a blocking mechanism. It stalls the process. Dr. Shapiro identified fears to include fear of the clinical outcome of

Example: It is not unusual for a client to express concern or fear that they are not “doing it” (i.e., the process) correctly or is afraid of extreme abreaction or that the clinician cannot handle the potential level of distress that they might express during the reprocessing.

Wellsprings of Disturbance

This phenomenon is indicative of “the presence of a large number of blocked emotions that can be resistant to full

Example: A man who is forced into therapy at the urging of a disgruntled spouse may possess the belief that “real men don’t cry.” This belief may be associated with an earlier traumatic memory and result in the client suppressing any high level of disturbance that might otherwise naturally occur under a current circumstance (e.g., dealing with his wife’s raging episodes). The true level of affective disturbance is never reached by the client, and it is this same level that contributes to the client’s present dysfunction. Earlier experiences taught him that men (or boys) are not allowed to express themselves emotionally. If there is no change in the client’s imagery, body sensations, or insight, but he continues to report a low level of disturbance, the wellspring phenomenon is probably in effect. When present, the clinician may need to provide additional

Blocking Belief = A negative belief about oneself that stalls reprocessing

Wellsprings of Disturbance = Negative Beliefs + Unresolved (Early Memories) + Blocked Emotions

The distinctions between wellsprings of disturbance and blocking beliefs are important because the presence of either determines what course of action a clinician may take to resolve the blocking issues.

Secondary Gain

A secondary gain issue has the potential of keeping a presenting issue from being resolved.

Example: Typical examples involve the following: what would be lost (e.g., a pension check); what need is being satisfied (e.g., special attention); or how current identity is preserved (e.g., “If I get over my pain, I’m abandoning those who have stood by me since the war.” Or, “If I lose my disability, how will I support my family?”).

Channels of Association

Within the targeted memory, events, thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations may spontaneously arise or arise when a client is instructed to go back to target (i.e., return to the original event [incident, experience]). These are called channels of association and may emerge any time during the reprocessing phases (i.e., Phases 3–6).

When cognition based, channels of association may be another level of the same plateau (responsibility/defectiveness or responsibility/action, safety/vulnerability, or power/control [or choice]) or can be another plateau entirely.

Example: Cara was in the middle of reprocessing being robbed (e.g., safety) after a movie one Friday night. After about five or six sets, she remembered that she had failed to zip up her purse while still in the theater when getting her keys out to drive home. She had a huge bank envelope largely visible for anyone to see (i.e., responsibility). When this channel cleared (i.e., continued to remain positive or remained neutral), the clinician took her back to target, and another channel of association emerged. Cara remembered seeing the robber in the movie theater and that he had been intensely staring at her. She decided it was nothing to worry about and went out to her car (e.g., choice, control).

Channels of association may emerge during reprocessing, where related memories, thoughts, images, emotions, and sensations are stored and linked to one another. The following example demonstrates a series of channels related to the client’s emotions.

Example: Cara was robbed after a movie one Friday night. After one set of

Now that you have a clearer picture of what these targets are and how they are related, can you think of examples for each? Recollect targets from some of your reprocessing sessions with clients to help you identify examples of each. Targets—past, present, future—especially ancillary targets, can emerge in any of the three prongs in the

BILATERAL STIMULATION

WHAT DOES IT DO?

When Dr. Shapiro was in the early stages of developing the theory, procedures, and protocol behind

A client’s preferred means of

If the information during reprocessing is not moving or becomes stuck, it is important to have the client agree beforehand on two preferred directions (i.e., back and forth, up and down, or diagonal) or two types of modalities (i.e., eye movements, audio, tapping) from which the client can choose. Thus, if a need for change in direction or modality occurs, the client has agreed to their preferences in advance. Any time a change in

PREFERRED MEANS OF BILATERAL STIMULATION

Shapiro’s (2018) preferred means of

Many studies have focused on investigating the role of eye movements in

Two dominant theories have emerged as a result of these research studies about the effects of eye movement during

Studies suggest that eye movements are superior to tones (van den Hout et al., 2012) and saccadic eye movements are superior on all parameters in all conditions to vertical eye movements (Parker et al., 2008). One study found that eye movements increased the true memory of an event (Parker et al., 2009). No research presently exists to support having the client process with his eyes closed. Lee and Cuijpers (2013) reported positive effects of eye movements in their meta-analysis.

Table 1.12 outlines the randomized studies of hypotheses regarding eye movements in

SHORTER OR LONGER? SLOWER OR FASTER?

During the Preparation Phase,

| 1996 Sharpley, C. F., Montgomery, I. M., & Scalzo, L. (1996). Comparative efficacy of |

| 1997 Andrade, J., Kavanagh, D., & Baddeley, A. (1997). Eye-movements and visual imagery: A working memory approach to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01408.x |

| 2001 Kavanagh, D. J., Freese, S., Andrade, J., & May, J. (2001). Effects of visuospatial tasks on desensitization to emotive memories. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466501163689 van den Hout, M., Muris, P., Salemink, E., & Kindt, M. (2001). Autobiographical memories become less vivid and emotional after eye movements. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466501163535 |

| 2002 Kuiken, D., Bears, M., Miall, D., & Smith, L. (2002). Eye movement desensitization reprocessing facilitates attentional orienting. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 21(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.2190/L8JX-PGLC-B72R-KD7X |

| 2003 Barrowcliff, A., Gray, N., MacCulloch, S., Freeman, T., & MacCulloch, M. (2003). Horizontal rhythmical eye movements consistently diminish the arousal provoked by auditory stimuli. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(Pt 3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1348/01446650360703393 Christman, S. D., Garvey, K. J., Propper, R. E., & Phaneuf, K. A. (2003). Bilateral eye movements enhance the retrieval of episodic memories. Neuropsychology, 17, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.15.3.515 Saccadic (not tracking) |

| 2004 Barrowcliff, A. L., Gray, N. S., Freeman, T. C. A., & MacCulloch, M. J. (2004). Eye-movements reduce the vividness, emotional valence and electrodermal arousal associated with negative autobiographical memories. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 15(2), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940410001673042 In testing the reassurance reflex model, |

| 2006 Christman, S. D., Propper, R. E., & Brown, T. J. (2006). Increased interhemispheric interaction is associated with earlier offset of childhood amnesia. Neuropsychology, 20, 336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894–4105.20.3.336 Servan-Schreiber, D., Schooler, J., Dew, M. A., Carter, C., & Bartone, P. (2006). In this study, patients with single-event |

| 2007 Parker, A., & Dagnall, N. (2007). Effects of bilateral eye movements on gist based false recognition in the DRM paradigm. Brain and Cognition, 63, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2006.08.005 Bilateral saccadic |

| 2008 Gunter, R. W., & Bodner, G. E. (2008). How eye movements affect unpleasant memories: Support for a working-memory account. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(8), 913–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.006 Support for working-memory account of the benefits of Lee, C. W., & Drummond P. D. (2008). Effects of eye movement versus therapist instructions on the processing of distressing memories. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(5), 801–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.08.007 Significant reduction in distress for Maxfield, L., Melnyk, W. T., & Hayman, C. A. G. (2008). A working memory explanation for the effects of eye movements in Supported the working memory explanation on the effects of Parker, A., Relph, S., & Dagnall, N. (2008). Effects of bilateral eye movement on retrieval of item, associative and contextual information. Neuropsychology, 22, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.136 |

| 2008 Bilateral saccadic |

| 2009 Parker, A., Buckley, S., & Dagnall, N. (2009). Reduced misinformation effects following saccadic bilateral eye movements. Brain and Cognition, 69, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2008.05.009 Supports hypothesis of the effects on episodic memory and interhemispheric activation. |

| 2010 Engelhard, I. M., van den Hout, M. A., Janssen, W. C., & van der Beek, J. (2010a). Eye movements reduce vividness and emotionality of “flashforwards.” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.003 In non-dual task condition and while thinking of future-oriented images, Engelhard, I. M., van den Hout, M. A., Janssen, W. C., & van der Beek, J. (2010b). The impact of taxing working memory on negative and positive memories. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 1, 5623. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5623 Compared Tetris to Kuiken, D., Chudleigh, M., & Racher, D. (2010). Bilateral eye movements, attentional flexibility and metaphor comprehension: The substrate of Found differential effects between |

| 2011 Engelhard, I. M., van den Hout, M. A., Dek, E. C. P., Giele, C. L., van der Wielen, J.-W., Reijnen, M. J., & van Roij, B. (2011). Reducing vividness and emotional intensity of recurrent “flashforwards” by taxing working memory: An analogue study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 599–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.01.009 Found with Samara, Z., Bernet M., Elzinga, B. M., Heleen A., Slagter, H. A., & Nieuwenhuis, S. (2011). Do horizontal saccadic eye movements increase interhemispheric coherence? Investigation of a hypothesized neural mechanism underlying In healthy adults, 30 seconds of bilateral saccadic Schubert, S. J., Lee, C. W., & Drummond, P. D. (2011). The efficacy and psychophysiological correlates of dual-attention tasks in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing ( van den Hout, M. A., Engelhard, I. M., Rijkeboer, M. M., Koekebakker, J., Hornsveld, H., Leer, A., Toffolo, M. B. J., & Akse, N. (2011). |

| 2011 Supports a working memory account of |

| 2012 Smeets, M. A. M., Dijs, M. W., Pervan, I., Engelhard, I. M., & van den Hout, M. A. (2012). Time-course of eye movement-related decrease in vividness and emotionality of unpleasant autobiographical memories. Memory, 20(4), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.665462 Supports the theory that emotionality reduces only after vividness has dropped. van den Hout, M. A., Rijkeboer, M. T., Engelhard, I. M., Klugkist, I., Hornsveld, H., Toffolo, M., & Cath, D. (2012). Tones inferior to eye movements in the In this study, |

| 2013 de Jongh, A., Ernst, R., Marques, L, & Hornsveld, H. (2013). The impact of eye movements and tones on disturbing memories involving Evidence for the value of employing Nieuwenhuis, S., Elzinga, B. M., Ras, P. H., Berends, F., Duijs, P., Samara, Z., & Slagter, H. A. (2013). Bilateral saccadic eye movements and tactile stimulation, but not auditory stimulation, enhanced memory retrieval. Brain and Cognition, 81, 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2012.10.003 Functional connectivity between the two hemispheres of the brain increased by bilateral activation of the same. |

| 2015 Kearns, M, Engelhard I. M. (2015). Psychophysiological responsivity to script-driven imagery: An exploratory study of the effects of eye movements on public speaking flashforwards. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00115 Using the control condition of imagery and van Veen, S. C., van Schie, K., Wijngaards-de Meij, L. D., Littel, M., Engelhard, I. M., & van den Hout, M. A. (2015). Speed matters: Relationship between speed of eye movements and modification of aversive autobiographical memories. Frontiers in psychiatry, 6(45), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00045 This study demonstrated that image vividness did not decrease emotionality over time. This is consistent with a working memory hypothesis that states that highly vivid images responded better to fast |

| 2016 Homer, S. R., Deeprose, C., & Andrade, J. (2016). Negative mental imagery in public speaking anxiety: Forming cognitive resistance by taxing visuospatial working memory. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 50, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.05.004 It was established as hypothesized that reduction in vividness of represented imagery (i.e., public speaking was visualized less vividly; generated less anxiety when imagined) was more effected by Sack, M., Zehl, S., Otti, A., Lahmann, C., Henningsen, P., Kruse, J., & Stingl, M. (2016). A comparison of dual attention, eye movements, and exposure only during eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for posttraumatic stress disorder: Results from a randomized clinical trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(6), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447671 When eye fixation and exposure control were compared to bilateral |

Abbreviations:

While using

During the Desensitization Phase, the suggested average number of

Some clients may require shorter or longer and/or slower or faster sets. For instance, clients who are anxious and/or unsure of the process may require longer sets of

| SLOW, SHORT SETS (4–6) Elicit a Relaxation Response (Slows Down the Train) | FAST, LONG SETS (24–36) Elicit an Activation Response (Speeds up the Train) |

|---|---|

| Safe (calm) place Resource development Resource development and installation | Reprocessing Installation Body scan Future template |

In terms of desensitization and speed, eye movements (or passes) that are too slow tend to stimulate a relaxation response and may not facilitate sufficient dual attention. Therefore, it is imperative for optimal processing that the clinician facilitates the passes as fast as the client can comfortably tolerate. In addition, the clinician should avoid long pauses between sets without a specific reason (e.g., the client feels the need for clinician connection). The client is discouraged from talking at any length between sets. It is suggested that the clinician minimally or nonverbally acknowledge what the client has reported and say, “Notice that” or “Go with that.”

Although the purpose of the Installation Phase is to fully integrate a positive self-assessment with the targeted information, there is still the possibility that other associations could emerge that may need to be addressed. The faster, longer sets of

Except for the reprocessing phases of treatment, shorter, slower sets of

Note: If a positive association occurs during reprocessing, do not slow the speed of the

CONTINUOUS BILATERAL STIMULATION

Although there may be clinicians who administer one continuous sequence of

Note: If a clinician uses continuous

| Provides an opportunity for the clinician to determine if processing has occurred based upon the client’s feedback. |

| Gives the client a break from processing, especially if a set contained an intense abreactive response. |

| Helps a client reorient in terms of present time and consequent safety (i.e., helps to keep “one foot in the present”) and thereby facilitates dual awareness. |

| Allows a client to share any new revelations or insights that arise during processing. |

| Allows a clinician to reaffirm a client’s experience throughout the process. |

| Enables a client to better integrate any new information that emerges on a verbal or conscious level. |

| Allows a clinician to continually reassess or judge the need for any additional clinical interventions or strategies. |

| Provides multiple opportunities for a clinician to give and a client to receive encouragement and reassurance. |

| In terms of abreactive responses, it solidifies for a client that they are larger than the disturbing experience and in control as they demonstrate they can approach and distance from the disturbance during these breaks. |

Abbreviation:

Table 1.15 lists what can happen if

| Using long and fast sets when doing stabilization Doing so may activate processing prematurely (i.e., speeds up the train) and cause a client to begin processing any dysfunctionally stored past memories or present triggers. Short, slow sets of |

| Using short and slow sets when doing reprocessing Slow, short |

| Note: Wilson et al. (1996) and Schubert et al. (2011) found that faster |

| Continuing with eye movements if a client reports pain or dryness because of the process If this occurs, switch to a previously agreed upon, alternate form of |

| Pausing too long in between sets There should be a specific reason for pausing too long between sets. Maybe the client is overwhelmed, “needs” to talk, or wants assurance that they are “doing it right.” If the client tends to relay everything that happened between sets, gently explain the information they give is for baseline reasons only (i.e., to let the clinician know where they are in the process), that the “mind is faster than the mouth,” and only minimal information is needed between sets. When a clinician or client talks excessively between sets, it inhibits the reprocessing (i.e., slows the train) of the targeted material. |

| During reprocessing, using sets that are too long or too short Using sets that are too long may cause a client to lose track of the primary event and become overwhelmed with too many thoughts, images, and emotions, and may inhibit or derail processing. Sets that are too short may inhibit processing by not giving a client enough time to initiate complete processing. The rule of thumb is to start with 20-plus sets of eye movements and judge from a client’s response (i.e., facial expression and body language) to determine what the appropriate number of sets is for each individual client. However subtle, a client will usually give a clue as to when a set is complete. |

| Using continuous Using continuous |

| Continuing with It is not uncommon for a client to look at a clinician and say, “Can we take a break right now? I need to say something.” In the event this occurs, simply stop the train and allow the client to unload any material; and restart the train when the client is willing and able. |

Abbreviation:

HOW TO DO EYE MOVEMENTS

Table 1.16 outlines the specific criteria outlined by Shapiro (2018) on the proper and acceptable way to facilitate eye movements in terms of preference, duration, speed, distance, height, and more.

| Before concentrating on emotionally disturbing material Initially using horizontal or diagonal eye movements, find the best fit for a client (e.g., horizontal, vertical, diagonal). Note: The vertical eye movements may be preferred if a client has a history of vertigo. It is also reported to be helpful in reducing extreme emotional nausea, agitation, eye tension, or dizziness. Vertical eye movements have been known to produce a calming effect. Experiment to find a client’s comfort level (i.e., distancing, speed, height). Switch immediately to an alternate form of Generate a full eye movement set by moving a clinician’s hand from one side of a client’s range of vision to the other. The speed of the eye movement should be as rapid as possible and without any undue physical discomfort to a client. Use at least two fingers as a focal point (i.e., two fingers held together is usually the preferred number in American culture). With palm up approximately 12 to 14 inches from a client’s face (i.e., preferably chin to chin or contralateral eyebrow, some say shoulder to shoulder), hold two fingers upright and ask a client, “Is this comfortable?” Note: It is important to determine distance and placement of the eye movement with which a client is the most comfortable prior to the Assessment Phase. Demonstrate the direction of the eye movements by starting in the middle and slowly moving the fingers back and forth in a client’s visual field, and then ending in the center. Evaluate and monitor a client’s ability to track the moving fingers. Start slowly and increase the rate of speed to the fastest a client can comfortably tolerate physically and still keep in their window of emotional intensity. Ask a client during this testing phase if they have any preferences in terms of speed, distance, and height prior to concentrating on any negative emotions or dysfunctional material. |

| After concentrating on emotionally disturbing material Listen to the client’s feedback to determine if adequate processing is taking place at the end of a session. If the client appears comfortable and shifts are occurring, maintain the predetermined speed. If the client is uncomfortable and shifts are not occurring, the clinician may need to adjust the speed, direction, and number of eye movements. If the client appears stuck (i.e., after successive sets of eye movements, the client reports no shifts), change the direction of the eye movement. If a client experiences difficulty (i.e., manifests in irregular eye movements or “bumpiness”) following a clinician’s fingers, attempt to assist the client to establish a more dynamic connection and sense of movement control that results in smoother tracking by instructing the client to “push my fingers with your eyes.” Assess the client’s comfort, preferred speed, and ability to sustain eye movements by listening to their feedback between sets. |

| If the client reports an increase in positive shifts, continue to maintain the same direction, speed, and duration. Note: If a clinician believes it might be beneficial, it is appropriate to experiment. However, a client’s feedback should be the final determinant whether to decrease or increase the duration of a set. Continue If a client experiences weakness in their eye muscles, they may be unable to do more than a few eye movements at a time. If a client is experiencing high levels of anxiety, demonstrates a tracking deficit, or finds them aversive, they may be unable to track hand movements. Note: If this occurs, reprocess the underlying experience of discomfort and, if need be, use the two-handed approach or auditory or tactile stimulation. The two-handed approach entails having the clinician position their closed hands on opposite sides of the client’s visual field at eye level and then alternating raising right and left index fingers while instructing the client to move their eyes from one raised finger to the other. This type of |

Abbreviation:

IS BILATERAL STIMULATION EMDR THERAPY?

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO CONSIDER

MEMORY NETWORK ASSOCIATIONS

No one knows what a memory network looks like, but these networks represent the basis of the

STOP SIGNAL

It is important to heed a client’s wishes to ensure a sense of safety in the therapeutic environment.

In the Preparation Phase, the client is asked to provide the clinician with a cue that indicates they want to stop the processing. It may be a hand, finger, or body gesture. The client may simply just turn away or hold their arms up in the air. Whatever the cue is, the processing should be discontinued immediately when used. This allows the client to maintain an ongoing sense of comfort, safety, and control. When this cue to stop is utilized, the clinician assists the client in accessing whatever is needed to stabilize the client and to proceed with the processing. Discontinue all

It is important not to accept words for stop signals (e.g., “Stop,” “No more,” “I can’t do this,” “I want to throw in the towel,” or “Whoa!”) as it may be confused with what is going on in the processing.

The stop signal is tantamount to having a cord on a train the passenger can pull to indicate to the engineer that they want the train to stop for some reason. For instance, the client may need an added rest before the next stop or may want to get off the train. Ultimately, it is the engineer (i.e., clinician) who stops the train when signaled by the client in some way to stop.

At the beginning of each session, the clinician may remind the client of the chosen stop signal by saying, “If at any time you feel you have to stop, raise your hand (i.e., remind client of desired stop signal).”

| “If at any time you feel you have to stop, (remind the client of chosen stop signal).” “Is this a comfortable distance and speed?” |

| Hand gestures |

Hand Signal Time-Out Signal   |

| Body gestures |

| Standing up Crossing arms or knees Putting hands over mouth, ears, or eyes Cyclist stop signal

|

EMDR Therapy Is Not Hypnosis

A frequent question asked by clients is, “Is

The differences between hypnosis and

WHAT ONCE WAS ADAPTIVE BECOMES MALADAPTIVE

Some behaviors are learned. Some serve us well and others do not. Some serve us for a period in our life and eventually become a nuisance. For example, a client who was repeatedly sexually molested by a relative as a young child may have learned to dissociate during the molestation. This was their automatic coping response to the fear and pain of the trauma at the time of the abuse. Years later, as an adult, they may still find themself dissociating during stressful situations in their work and life. As a child, dissociation was the only response available and allowed them to cope; it worked well at the time. As a maturing adult, the dissociation begins to cause problems at home, at school, and/or at work.

DEVELOPING AND ENHANCING ADAPTIVE NETWORKS OF ASSOCIATION

Before processing of the negative networks may begin, clients with more complex cases may need to access, strengthen, and reinforce positive life experiences and adaptive memories (e.g., positive resources and behaviors, learning, self-esteem). It is possible to access these positive experiences by developing new and enhancing existing positive networks described as follows.

| HYPNOSIS | |

|---|---|

| Integrative psychotherapy model. Efficacious treatment for Bilateral eye movements are utilized. | Medium within which Case reports available that suggest the efficacy of hypnosis for trauma treatment outcomes (Cardena et al., 2009). Bilateral eye movements occur in hypnosis, but usually are ignored (Bramwell, 1906). Theta (Sabourin et al., 1990), beta (De Pascalis & Penna, 2009), or alpha (Meares, 1960) waves are characteristic of hypnotized subjects. |

| During desensitization, the client may be in a state of heightened emotional arousal. | After induction, the client usually is in a deep hypnotic state. |

| Clinician follows a set procedure and generally does not include clinician-generated suggestions (i.e., lacks suggestibility; Hekmat et al., 1994). | There is no set procedure and includes clinician-generated suggestions (i.e., encourage suggestibility). |

| Each set of eye movements lasts about 30 seconds. | Client is in a trance lasting anywhere from 15 to 45 minutes or longer. |

| Memories may emerge, but memory retrieval is not the primary purpose. | Is often used for memory retrieval. |

| Images of memories generally become more distant and less vivid, and more historical. | Images of memories are generally enhanced and made more vivid and experienced in real time. |

| Clients tend to jump from one associative memory to another. | Clients follow a moment-by-moment (“frame by frame”) sequence of events. |

| Eyes are usually open. | Eyes are closed throughout the induction and treatment phase. |

| Uses | Does not use |

| Clients appear more alert, remain conscious, and are less susceptible to inappropriate suggestion. | Clients are less alert, not conscious, and more susceptible to suggestion. |

| Does not induce a trance state. | Induces a trance state. |

| Dual focus of attention is deliberately maintained at all times. | Dual focus of attention may occur (Harford, 2010). |

| For long-term trauma issues, duration of treatment is often brief. | For long-term trauma issues, duration of treatment is often lengthy. |

Abbreviations:

Developing New Positive Networks

(a) New positive experiences are created when the clinician teaches the client safe (calm) place and other stress management and relaxation techniques; (b) the initial introduction of

Enhancing Already Existing Positive Networks

Investigate and determine what positive life experiences and adaptive memories already exist. As the client holds these positive experiences in mind, the clinician implements

Example: Adalia presents with a history of anxiety. The clinician asks the client to imagine a time in her past when she felt empowered and safe and instructs her to imagine how it might have felt to look, feel, and act that way again in a positive way. As she imagines this positive image, the clinician initiates short and slow sets of

Regardless of how and when they come about, it is important for these positive networks to be present and accessible for reprocessing to occur. With clients who have trouble in identifying positive networks of association or role models, plan on a longer preparation time before any processing of negative experiences.

STATE VERSUS TRAIT CHANGE

Shapiro (2008) differentiated between state and trait change. She defined a state change as momentary or transitory, whereas a trait change reflected a permanent change. A state change is a change of mind. It instills a sense of hope in the client. A state change also requires the use of coping mechanisms to continue the change, whereas a trait change no longer requires the same. With a trait change, the client changes how they see or view the event and, as a result, can experience it differently.